10 Questions with Jennifer Harris

A few years ago, I forced myself to do a thing that scared me. I reached out to a local author I admired, Heather Smith, and asked if she maybe, perhaps, by any chance might possibly be willing to have coffee with me. I really didn’t expect her to say ‘yes,’ but she did, and we met, and she was both lovely and generous.

A few months after that, I got an email from Heather saying that she had been contacted by a few different aspiring and emerging writers who were each looking for a writing group. Would any of us be interested in meeting each other?

And that is how the Kid Lit writing group I belong to was formed. Because it was the height of the pandemic, we only met virtually, and, because we each lead busy lives and two of us don’t drive, we have continued to meet that way even as life has begun to open again.

One of those writers was Jennifer Harris, an English professor and scholar at The University of Waterloo, who had recently sold her first picture book. We were a good match in the sense that we were at a similar stage in our writing journey, but we soon learned that our compatibility went much deeper than that. We both loved food, enjoyed a good cocktail, and were drawn to writing that combined a lyrical attention to language with a quirky sense of humor. We were also each trying to out eke out the time and space for our creative work while pandemic-parenting a pair of children.

Although we live in the same city, we only recently met in person for the first time. Despite this, Jennifer is someone I have come to think of as a colleague, a mentor, and a genuine friend. She is a truly excellent critique partner with a formidable depth and breadth of knowledge about the history of children’s literature and uncanny ability to ask exactly the right questions to push a story forward. She is also someone I find myself texting whenever I am struggling to navigate the sometimes-opaque waters of the literary world, or when I just need someone to commiserate with over a yet-another particularly painful rejection.

Jennifer Harris is the author of She Stitched the Stars (Albert Whitman, 2021). Her next books, When You Were New (Harper Collins, 2023) and Keeper of the Stars (Owl Kids, 2024), are forthcoming.

1. Were you a bookish kid? What role did reading and writing play in your life as a child? Were there specific books that made a mark?

JLH: I was that child who walked down the street reading. I read in the car, I would’ve read at the dinner table if it was allowed. I even showed up at Girl Guide camp with a suitcase stuffed with books and a radio—other campers gathered to watch me unpack, because they couldn’t fathom anyone thinking to pack those things. If the books made me seem odd, though, the ability to play music more than made up for it!

In terms of books that made a mark, The Westing Game is one of the most perfect novels I know. Turtle Wexler is a brilliantly relatable protagonist, on the edge of her world, but seeing more of it than people give her credit for. And the way Raskin represents adults as these flawed but decent humans was so illuminating. If I’m in a used bookstore and see a copy, I’ll buy it, just to have a copy to give away. Lucy Boston’s The Children of Green Knowe was also a favorite. That book is embedded in the notion of historical continuity, celebrating permanence and place through a single ancient house. There’s something about the security Tolly found at Green Knowe that profoundly resonated with me. There’s a butler’s mirror hanging in our house because there was one in Green Knowe, and there are netsukes on our windowsill because they featured in Green Knowe. Books, for me, conveyed security, and turning my house into a bookish house has been a way of reproducing that.

I take Jennifer’s book recommendations very seriously. When she mentioned this one, I set out to order it immediately. When I discovered there was an edition with an intro by Mac Barnett, I knew it was fate.

2. You are also an English professor at the University of Waterloo, specializing in 19th century American literature. Do you see those two roles and practices as connected, or are they totally separate animals?

JLH: As an archival scholar, I search for lost writers, and bring their stories to light. In that sense, I’m constructing narratives based on what is often a scarcity of materials. It’s also a somewhat political project, as I most often work on women and Black North American subjects whose lives have been undervalued. So finding a way to respectfully honour them is important. And then I send these findings into the world, where they become the property of other people and the communities who might claim them. There’s a need to be accountable both to the subjects themselves, and to the communities from which these writers came.

This sense of accountability carries over into writing for children. On the one hand, this means that most of the stories I excavate for academic publication are not mine to tell in picture book form. But more than that, it’s about being accountable to the reader and to the story I’m telling, and ensuring it’s being told in the right form, and thinking about the choices one makes in telling any story. You can’t just shove something into a form—you have to follow the material itself.

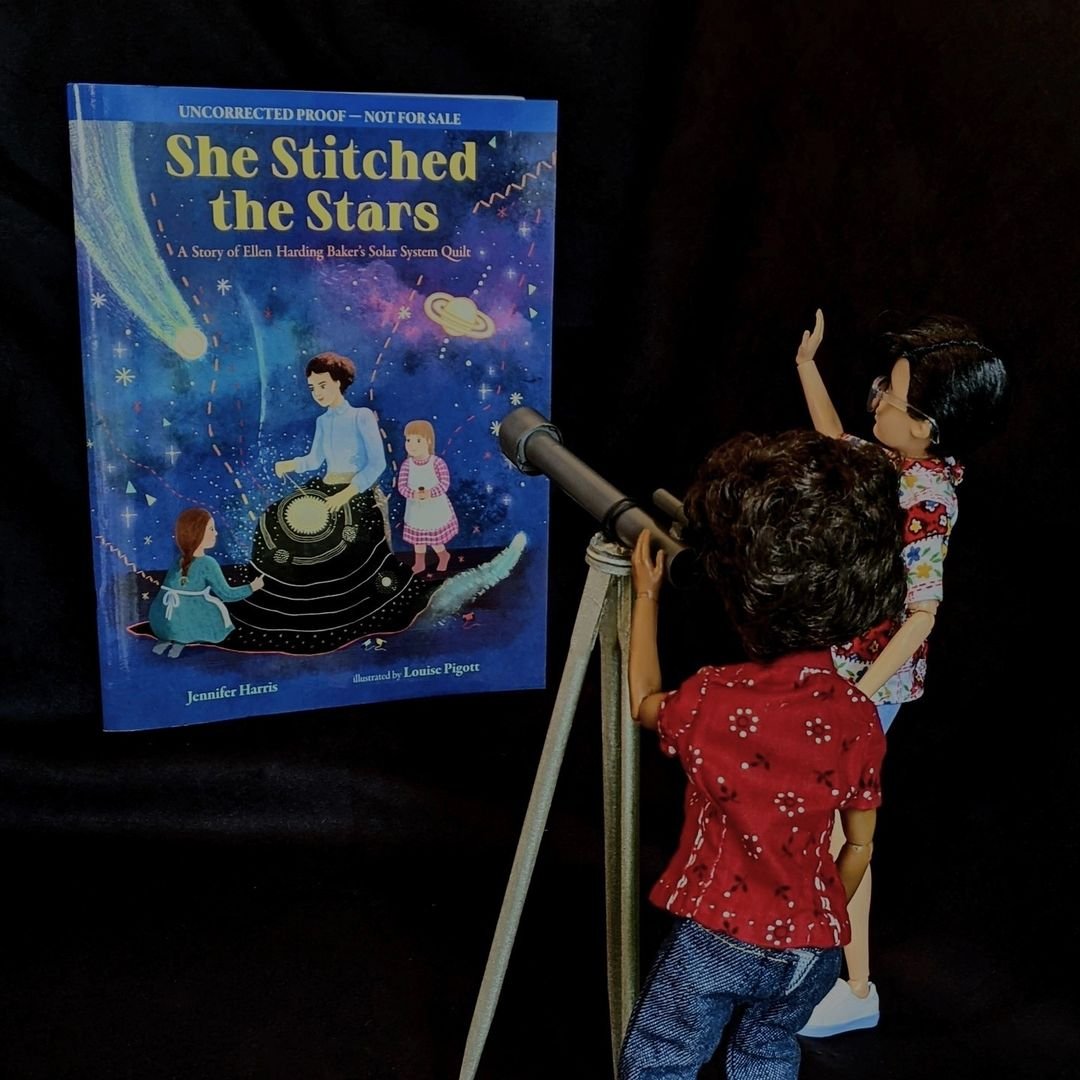

3. Your debut picture book, She Stitched the Stars, tells the story of Ellen Harding Baker, a storekeeper’s wife and mother from Iowa who, beginning in 1876, creates a quilt that accurately depicts the solar system. What was it about her story that compelled you to tell it in this form?

JLH: Ellen Harding Baker’s story is wonderful, and I knew immediately I wanted to write about her, but also that an academic paper wasn’t the right form. So little of her life was preserved—in part because people didn’t fully appreciate her achievement, but also because women’s lives weren’t often seen as worthy of preservation. A creative piece seemed the ideal way to get around the lack of materials while also conveying the spirit of her endeavor. I could compensate for what we didn’t know by working with what we could take for granted—that seasons changed, there was gardening, and babies kept arriving, all the while she was trying to complete this quilt. Without thinking about it, I started writing it from the view of her children—it made for a better story, one with more opportunities for play.

4. One of the wonderful gifts of getting to read so much of your work has been the opportunity to immerse myself in a picture book genre I have yet to tackle myself — the picture book biography. You are so skilled at weaving historical facts into narratives that feel alive with sensory detail and poetic language. You are able to take the stories of people who may have historically been overlooked and create narrative portraits of their lives that feel so real and full I can’t help but care about them. How do you think about writing in this genre? Are there other books or authors have informed you approach?

JLH: Thank you for such kind words! This might be where being an archival scholar helps. When you deliver papers on archival work at academic conferences, you see firsthand what hooks people about a historic figure. It’s often something unexpected and intimate—the cost of a dress, a piece of gossip, a comment about who lived next door. You have a historical arc, the story you need to tell, but it’s the more intimate moments that people latch onto. For me, the best picture book biographies are structured around these details, which keep it from feeling like a history lesson. Really, fewer dates and facts, more immediacy. There’s a reason back matter exists.

“ When you deliver papers on archival work at academic conferences, you see firsthand what hooks people about a historic figure. It’s often something unexpected and intimate—the cost of a dress, a piece of gossip, a comment about who lived next door. You have a historical arc, the story you need to tell, but it’s the more intimate moments that people latch onto.”

In terms of other writers, at one point I had a stack of forty or so picture book biographies piled beside a chair, and started to get very particular. Kyo Maclear does beautiful books that you can read aloud, and which have layers of meaning. It’s not simply “they persevered” cheerleading, there’s more in there about the texture of life. Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat by Javaka Steptoe is brilliant and tremendously compassionate. It’s also a master class in how you write about someone whose life maybe didn’t turn out as planned. It won the Caldecott for good reason. Dave the Potter is a wonderful example of how to tell the story of someone whose life wasn’t valued—Dave was enslaved in South Carolina, and inscribed poetry on his pots at a time when literacy could be life-threatening. And, of course, everyone loves Mac Barnett’s The Important Thing About Margaret Wise Brown, which plays with the form in innovative ways in order to capture her spirit. Of course, I would also argue that only someone in Barnett’s position could get away with that innovation.

She Stitched the Stars has pride of place in my growing collection of picture book biographies.

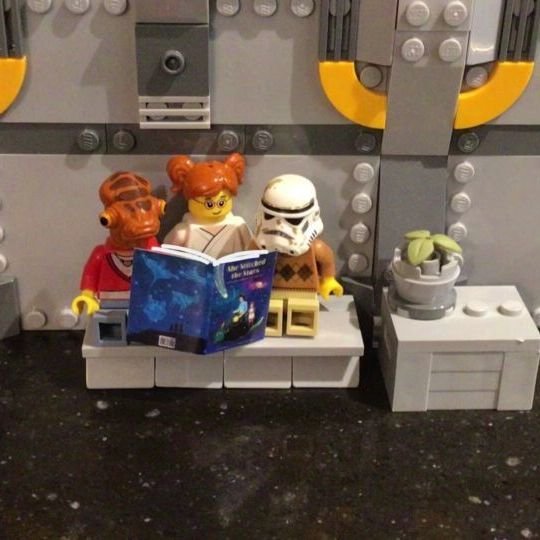

5. Your book, like so many others, launched in the midst of a pandemic that prevented you from promoting it in traditional ways. While so many others choose to go the route of the Zoom launch, you did something totally different. You created an amazing “virtual tour,” creating dozens of Instagram posts featuring meticulously crafted vignette’s populated by Barbie dolls enjoying your book in all sorts of spaces and situations.

I love that you chose a fun and novel way to promote your work that also felt incredibly organic to your subject matter in that it involved you crafting physical works of art with the help of your family, just like Ellen Harding Baker did. It was also such a genius way to keep your book in your IG feed week after week without ever coming across as hitting your followers over the head with repetitive content—every post offered something fresh and impressive! And as much as we all want to continue to support artists and writers during this time, so many of us are Zoom-ed out! Can you talk a little bit about how you conceived of this project, and what it has been like to work on it? What are your hopes around publicizing your next book, When you Were New, which will be released in 2023?

JLH: What’s the expression? Necessity is the mother of invention? I think we can agree mothers working full-time from home in a pandemic without childcare had a surplus of necessity. In this case, everyone said I should be on Instagram to promote my book, and I had children at home who needed something to do. So we started using their toys to create scenes featuring the book. We would come up with an idea, and then I would send them on a scavenger hunt around the house to find things they could use or transform into a scene. There was paper mâché, and scenic painting, building things from Lego and clay, sorting through scrapbooking paper we’d inherited. In the end, dolls proved the most versatile. People have generously loaned us their childhood doll furniture, or miniature designer chairs (thank you architect!). Otherwise, the goal is to make as much as possible, and we always list the materials—our recycling figures prominently. Interspersed are photos of other picture books and comments about writing.

I get what you’re saying about some writers essentially posting their book over and over. My feeling is that in order to be genuine, whatever I do has to add value. The scenes make people smile; they try to figure out how things were made. That’s my goal for the launch of When You Were New (HarperCollins)—whatever I do, it has to add value.

6. Speaking of your next book, it is quite different from She Stitched the Stars in that it is not a historical biography. Can you talk a little bit about the process of writing this one?

JLH: Sometimes a line comes into my head, and if it’s good, I’ll pause and play with it. In the case of When You Were New it was a line about how, when you were new, there were things you didn’t know. I knew my youngest would find the concept inherently funny—babies don’t know so much! But the idea also has an emotional resonance for parents, as you watch a child grow and learn, and think about how much more they will grow and learn. So it began as this piece about all the things an infant might not know, but might encounter over the course of a day, morning to night. I was fortunate my agent, Jackie Kaiser, liked it, and had useful feedback. Then it got into the hands of the wonderful editor Tamar Mays, who had the vision of the child growing over the course of the story. Finally, Lenny Wen brought it to life with delightfully whimsical and sensitive illustrations. She conveys such a sense of discovery, and enriches the text’s gentle humour.

7. Gaspereau Press recently published your first collection of poetry for adults, a beautiful chapbook titled Poems for Reluctant Housewives. It is full of sharp, visceral evocations of domestic themes and imagery that read as equal parts wry and menacing. What were you trying to communicate in these pieces? I know from our previous discussions about this work that it is emphatically not autobiographical, but how do you conceive of the narrative perspective(s) at play? Whose voice(s) are you trying to capture?

JLH: Walking around the neighborhood early on in the pandemic, I would think about all of these silent houses, and what was going on within. Especially as we were hearing reports about how advances for women were being rolled back by decades, and divorce rates were rising as couples were suddenly forced to spend time together. I started to imagine the frustrations, and think about 1970s feminist poetry and that sense of being trapped. At the same time, it was important to me that any poetry not be tied to a resentment of maternity or husbands. Instead, the frustration is with the claustrophobia of the pandemic and the life choices it might make one confront. Do you, as a forty-five-year-old, regret letting twenty-five-year-old you pick your spouse? Did you really believe shiplap would bring tranquility? Do you function best as a couple when you have an audience? Gaspereau understood the wry humour, and gave me a cover that conveyed that.

8. One of the surprising silver linings of the pandemic has been the literary friendships I have forged, including ours. I have been so lucky to have found such a sharp-eyed, thoughtful critique partner.

One thing I so admire about your feedback is that it always comes from a place of you trying to understand what I am trying to do, and helping to move the manuscript towards a clearer expression of that intent. You ask the best questions, which always prompt me to delve deeper. What do you think makes for a great critique group or partnership?

JLH: The feeling is mutual! You have a tremendous understanding of the field, and are deeply invested in discussions of craft and process, which is such a gift in a critique partner.

Our group is interesting, because we’ll have an extended conversation about why something isn’t working. Some people might see that as a personal attack, spending time unpacking what doesn’t work—I think it succeeds because we recognize that figuring out why something doesn’t work is key to a better understanding of the manuscript overall and what it actually does need. For me, that signals that we trust each other, and respect the differing expertise each of us brings to the table. The keywords in that last sentence—trust, respect, and expertise—are probably the most crucial things. Though an ability to commiserate about the idiosyncrasies of the industry is also exceptionally welcome.

9. I am somewhat nosey when it comes to other creatives’ workspaces and processes. Can you share a bit about yours? Where do you write, and when? What rituals, tools, and/or snacks do you need in order to get down to work?

Those precious few minutes in bed in the morning can be really productive, before anyone asks you for anything. I can play with sentences and words. The shower is also one of those spaces where I can generate a line or two that works, as long as no one decides they need to brush their teeth that very minute, or pops in to ask where their lunch bag is. For me it’s less about a physical space than it is having mental space when there are no immediate demands. I can steal time to write from other tasks, but I have to know that there isn’t an imminent interruption. That said, I’d be terrible at sitting down at a set time every day and making myself write. The end product would feel forced.

The idea of snack rituals is intriguing and not something I’d considered. Maybe I’m more of a snack distraction writer?

10. One of the things our writing has in common is that it often is very food-focused. What foods brought you the most comfort as a kid? How about now?

JLH: My holdovers from childhood are chocolate and cheese and chowder and spanakopita. I’m pretty sure I could survive on those indefinitely if allowed. I know modeling good eating for the children is important, and try to make sure we eat well, but it’s not my first impulse. I’d rather grab a wedge of cheese than an apple. I recently heard myself say “you can’t just eat a brownie and call it lunch.” I’m not sure whose mother I’ve turned into, but it’s certainly not mine.

11. If you could throw a fantasy dinner party with any 10 people, living or dead, who would you invite? What would be on the menu? How about the playlist?

JLH: I was talking about this with a friend and she quipped “you know, so many of those guys from history would end up getting drunk and handsy” and it’s entirely true. And their politics would be abysmal. But after how long in the pandemic, the truth is I just want to see my people. I’d love to invite my friends, some of whom have never met. Ideally it would be a buffet that forced people to constantly get up and move around and enter new conversations. Maybe something smoky and retro like Shirley Horn or Julie London playing. And it goes without saying that it would have to be catered, because I would want to spend all my time with the people I love. Which I guess means my partner and children make the cut! Clearly ten seats won’t be enough.